I assume not everyone has been glued to their TV watching the Ken Burns epic all this week on PBS on National Parks: America’s Best Idea. Whether you like his filmmaking or not, the narrative and history of our parks and how they were preserved was enlightening and stunning to watch. Peter Coyote told us the other night that Jimmy Carter had bypassed Congress during the fight to expand protected land in Alaska and invoked the Antiquities Act in 1978 to create 17 national monuments covering 56 million acres. It’s startling to remember that Carter was fighting powerful commercial interests; the discovery of vast oil deposits and the gas pipeline had brought jobs and the promise of a strong economy to Alaska.

But Carter and Morris Udall, his Secretary of the Interior, knew that counting on oil lasting forever would be irresponsible. The parks and wildlife were their focus and everyone should be thanking Carter for his prescience.Â

‘…it was still the largest single expansion of protected conservation lands in world history. The national park system, with 47 million acres added to its care, had suddenly more than doubled in size.’

What I liked best about the series was his inclusion of historians, writers, activists and Park Rangers themselves. These intimate stories really tell the mystery of nature’s allure and why as a culture we need to preserve it. Almost every tale about preservation had as its backbone a wealthy or thoughtful philanthropist who fought to protect wildnerness. At the same time, iconoclasts like John Muir and Adolph Murie stubbornly continued, despite conflict and opposition, to evolve standards of conservation that brought back wildlife and eliminated developers’ plans.

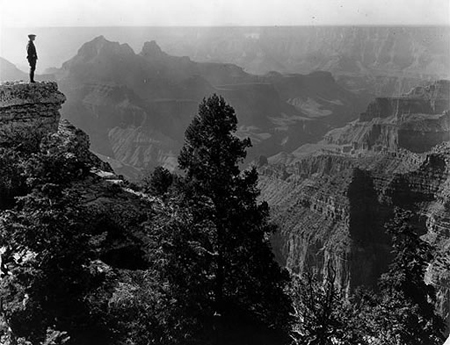

Like one of the historians who talked about an early parks adventure in the back of the family station wagon, my dad took us on an almost month long cross country trip back in 1961 to visit various National Parks along the way; The Grand Canyon, the Petrified Forest, the Painted Desert, Santa Fe National Forest and the Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument in the Gila Wilderness.

Sante Fe back then was nothing like I imagine it is now, more dusty and sleepy. I remember buying a turquoise and silver ring from an elderly Native American woman selling jewelry on the plaza. Â Then when we got to Los Angeles and my father’s boyhood home in Hollywood, he took us to see the La Brea Tar Pits where woolly mammoths, sloths and saber-toothed cats from 38,000 years ago have been preserved in black gook.

Â

I remember all of it and how stunned I was standing on the edge of the Grand Canyon looking down into the gorge below. It took my breath away and I wanted to dive into the air with joy. It was the beginning of my fear of heights – because they attracted me so much.Â

The abandoned little cave dwellings in the Gila Wilderness- that seemed as though you might walk out to make your coffee in the morning and accidentally slide down the edge of a cliff. I remember thinking how physically small the inhabitants must have been. These were tiny abodes even in comparison with West Village apartments.

The final destination for us three kids was of course, Disneyland. It had opened just six years earlier and we were determined to have a blast.Â

The point that hit home from Burns’ extravagant documentation is that most of my inspiration as a painter has come from nature. I’ve done my share of figurative work and the human form still holds interest. But on many levels, nature is where my work comes from and the paintings demonstrate a deep, direct and emotional response to place. Over the decades, I’ve travelled to many remote, usually mountainous areas on painting trips. The Rockies, Vancouver Island and the northern coasts of California and Oregon have been some favorite regions for more recent solitary exploration and studies.

Â

In my twenties I bought a 40 acre undeveloped paradise in western Maine and planned to create a utopian farm/art studio on top of a mountain facing Mt. Blue State Park. The coast had Acadia, but central Maine had Katahdin in Baxter National Park. The land was sold years ago, but the dream to protect a large swath remains.

The Great Smokies was one of my favorite areas for mini sketching trips when I lived in Atlanta for twenty years. Mount Mitchell in North Carolina, the Shenandoah National Park in Virginia, I hiked through most of the South’s parks and mountain ranges.

I have to think that the genesis for this highly charged connection can be traced back to that early trip when I was eleven, standing at sunset watching colors seep over the New Mexico desert, or the cerulean blue of an Arizona sky over the Grand Canyon. I plan to dig out my old VHS copies of his 8mm film of that trip and reminisce.

It was moving to see most of the other historians and writers in the series tear up when recalling similar childhood trips with their families to these spectacular monuments.

Thanks, Dad.

…my father was a film editor who worked on the 1945-49 Nuremberg Trials documentary, now in the Library of Congress.

thanks for sharing the photos, and paintings. What a tremendous blessing that these natural wonders belong to US — all of us, and we all have access to them. A reminder of how much there is to explore here at home.

Wonderful essay. What I loved about the series was the focus on how individuals made a difference. The depth of caring and determination was astonishing. But the single most affecting moment was when someone said the future of the parks is never permanent; like our civil rights, their future requires vigilance. We’re already planning our cross-country trek!

Agreed- what especially got to me too was that if not for a few determined and very stubborn people, we wouldn’t have these parks today.

Not only the rich with friends in high places, but also the pitbulls who simply refused to compromise.