I haven’t been able to find many glowing reviews of this 1964 film and it seems to be misunderstood on almost every level. Most reviewers portray the director, Arthur Penn, as having failed at his task of creating a coherent narrative and Warren Beatty as being ‘energetic’ but miscast as the lead. As one of the few supportive mainstream critics, Judith Crist loved the film, calling it ‘a brilliant original screen work’. I felt the same way when I watched it earlier this evening on Crackle.

Penn offers a multi-layered work of art that incorporates new wave and experimental film techniques new at the time, such as layered clips and double exposures. He adds an iconic beckoning character who keeps popping up during Mickey’s darkest moments; a Japanese performance artist who uses a horse and wagon to drive his sculpture around the city. This is fairly transparent symbolism – the artist as grinning clown who seems to live only for his art – but the scenes still serve as a bridge to the lead character’s final revelation.

The plot lays bare neurosis and paranoia; the general state of the country coming out of the McCarthy era and the communist ‘menace’, and heading into the Viet Nam war. Penn admits in one interview that he wanted to capitalize on the original play’s exposé of the era’s ‘timidity’ and ‘sense of guilt and a sort of silence and evasion’. In another interview he denounces the fear of communism as nonsense, saying that the American people knew better. In other words, it was obvious propaganda from a government using scare tactics to control its populace. His Mickey was running ‘from allowing other people to have possession of you.’

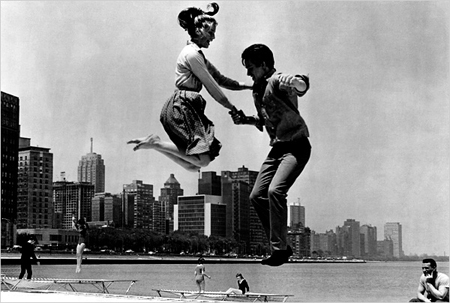

Everett Collection

The jazz score by Eddie Sauter and Stan Getz‘s sax improvisations plays to a voiceless fight scene in much the same way that Penn would use an excruciatingly slow shutter speed three years later for Bonnie and Clyde’s final denouement. The contrast of the beauty of music and motion to violence is what makes his films’ violence seem so completely detached from reality. In much the same way that audiences detach and become numb when they watch any violence at all.

Penn must have been impressed by the surrealism and wide shots of Antonioni’s Red Desert from a year earlier. His close-ups of cars being crushed (often with bodies still inside) and girders framing Beatty are reminiscent of that film’s wide angles of a nuclear power plant and the existential bleakness of its own industrial landscape. Robert Bresson’s cinematographer, Ghislain Cloquet, was hired to shoot Mickey One in black and white, because as Penn said, it was essentially ‘a colorless’ film.

Panned by Bosley Crowther in a 1965 NY Times review, the film should have garnered more acclaim, not least for Penn’s resistance to a Hollywood pat theme of good triumphing over evil. What we’re given is compromise, that ubiquitous and not very dramatic solution to a human dilemma. The mob has either given up chasing Mickey or they’re willing to let him go through life as a mediocre talent. Apparently he’s no longer important enough to be wiped out. And Beatty’s character has given up running. He chooses to live one last evening (a small courage) on stage rather than to keep living in fear. His last words on screen are ‘or is that the word?’

Thanks for the brilliant insights into the film, one I’d never come across, and the era it represents. I’ve put Mickey One on my “must watch” list.