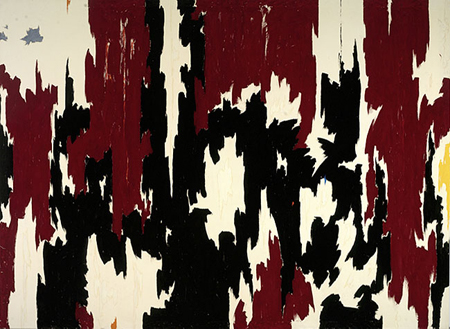

Clyfford Still is one of the more odd abstract expressionists. His huge canvases remind me a little of a Brothers Grimm fairytale or something shaggy, like no knead bread before you bake it. There’s an intense life force in his work- you could call it energy- to which I respond. A true iconoclast, he had an unerring belief in his talent and uniqueness. In fact, he kept most of his paintings, which is a revelation. If we’re any good as artists, we know our own worth and yet this is something most of us don’t do. We either blithely give them away to friends and family, or if we’re lucky, sell the bulk of them.

95% (169) of Still’s were rolled up and found in pristine condition after his death in 1980, protected from the public and dealers by his widow. In his will, he stipulated that all of his work be bequeathed to an American city that would “build or assign and maintain permanent quarters exclusively for these works of art and assure their physical survival with the explicit requirement that none of these works of art will be sold, given, or exchanged but are to be retained in the place described above exclusively assigned to them in perpetuity for exhibition and study.â€

Denver is that city and the museum, opening in 2010, will be devoted entirely to Still’s works.Â

As a critique to hoarding paintings, my pal Marty offers this:Â

When a known artist dies, the IRS comes in and taxes the remaining work at their latest sales values. So, if his were going for, say, 50k apiece at the time of his death, his wife and kids had to pay a really hefty income tax on that basis. Which is why some artists’ widows, largely male artists in the past, have had to dump all of the surviving work onto the market all at once, depressing their overall value and thereby pissing off galleries, collectors and museums.Â

Which is also why we’ve heard in the recent past of very old artists destroying all of their work before they die, so as not to saddle their estate with the tax burden. And also why, rumor has it, that Jasper Johns only paints about 4 paintings a year, to keep their prices up and limit estate liability…. though he’ll clearly never have to worry about how his wife will deal with it.

Sylvia Hochfield in  January’s Art News offers a superlative review of Clyfford Still’s work and even describes his painting techniques, excerpted here.

‘“Still had only so many stretchers,†his daughter Sandra said. “He had to roll up the paintings so he could do the next work. There were surges of energy in the months that he could paint.†The artist worked in the barn of his farm near Westminster, Maryland, and it was not usable in winter. “He had to go to the next and the next. The works evolved from one to another.â€

But Ramsay said that Still did it right. It’s counterintuitive to roll a canvas with the paint layer facing outward, as he did, but in fact it’s much safer. Still rolled as many as eleven canvases together, with nothing in between, around a cardboard tube or, in a few cases, a metal drainpipe; he then secured the roll with masking tape, wrapped it in plastic sheeting, and stored it vertically. When Ramsay and her team unrolled the canvases, they discovered that some paint layers were still tacky.

Still emerged in the ’50s as, in Hess’s words, “one of the strongest and most original contributors to the rebirth of modern art in America.†That description wouldn’t have pleased the artist, who saw himself not only as the strongest and most original but as a heroic figure whose achievement surpassed the realm of art.

The galleries of the ’40s and ’50s, with their “gas-chamber white walls,†were nothing but “sordid ‘gift-shoppes,’†Still wrote in the catalogue for his Met retrospective in 1979. But in two of those galleries—presumably Art of This Century and Betty Parsons—“was shown one of the few truly liberating concepts man has ever known. There I had made it clear that a single stroke of paint, backed by work and a mind that understood its potency and implications, could restore to man the freedom lost in twenty centuries of apology and devices for subjugation.â€

In 1959 Still held a retrospective at the Albright, with 72 paintings chosen by himself. In a letter to museum director Gordon Smith that was printed in the exhibition catalogue, Still made even larger claims for his art. After lamenting the corruption of institutional culture and describing his own lonely journey to the “high and limitless plain†where imagination “became as one with Vision,†he quoted William Blake and then warned, “Therefore, let no man undervalue the implications of this work or its power for life;—or for death, if it is misused.â€

With the eloquence of an Old Testament prophet, Still poured out his loathing for the art establishment; critics, curators, collectors, dealers, and other artists were all the objects of virulent denunciations. He didn’t give his paintings titles because that would have encouraged the interpretations he deplored. He disliked group exhibitions because they put him in the context of other artists or suggested that he was part of a school. When curator Dorothy Miller persuaded him to participate in the landmark “15 Americans†exhibition at MoMA in 1952, he insisted that his works be shown in their own room.

Still sold fewer than 180 paintings—enough to allow his family a modestly comfortable life. He made two large gifts to museums, presenting 31 works to the Albright (now Albright-Knox) Art Gallery in Buffalo in 1964 and 28 paintings to SFMOMA in 1978. In 1986 Patricia gave ten paintings from her collection to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which had organized a Still retrospective in 1979. The conditions of all three gifts were strict: Still’s paintings had to be exhibited together in one room. They could not be shown alongside the works of other artists. They could not be sold or lent to other museums.

In Still’s own words:Â ‘These are not paintings in the usual sense. They are life and death, merging in a fearful union.’