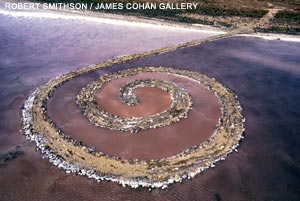

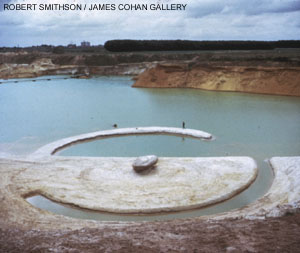

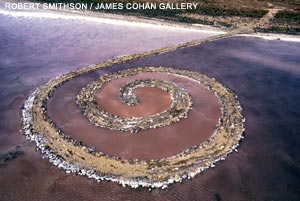

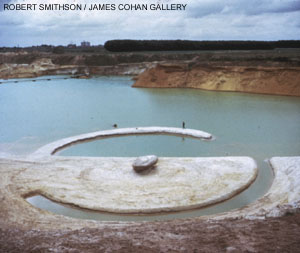

In this week’s New Yorker, Geoff Dyer’s Poles Apart tells the story of a pilgrimage to the land art created by Robert Smithson and Walter De Maria in the 1970’s; Smithson’s Spiral Jetty at the Great Salt Lake in Utah and De Maria’s The Lightning Field in rural New Mexico. He doesn’t at first identify the artworks, but describes ‘a homesteader’s cabin and a windmill, in the middle of a vast nowhere’. Those of us who can recall when these pieces were first created might guess his subjects.

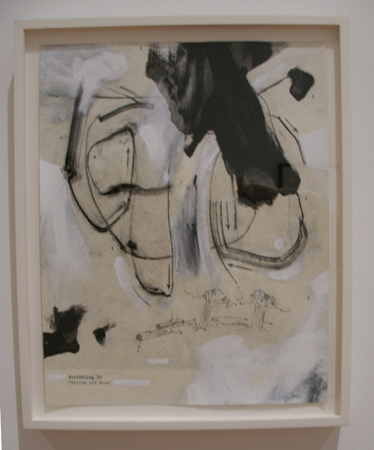

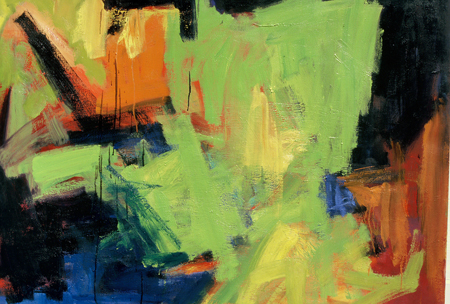

I never paid much attention to either the intent of these artists or the works themselves; I had always been more interested in painting and its own messy and fine tradition.

But recently, as I began considering ideas for a public art project, these first generation land conceptualists crept into my consciousness. Why did they choose the earth and its bodies of water, desert or mountains as their material of choice and what did these monolithic designs mean to them? Dyer focuses more on De Maria’s quest for the ‘appropriate spot’ and light’s meaning in the work, but he doesn’t try to uncover either artist’s motivations.

Walter De Maria, The Lightning Field, 1977. Long-term installation in

Western New Mexico. Photo: John Cliett. Copyright Dia Art Foundation.

Walter De Maria was born in California in 1935 and grew up in the Bay Area. Here’s the Wiki entry for his most famous work: It consists of 400 stainless steel posts arranged in a calculated grid over an area of 1 mile × 1 km. The time of day and weather change the optical effects. It also lights up during thunder storms. The field is commissioned and maintained by Dia Art Foundation.

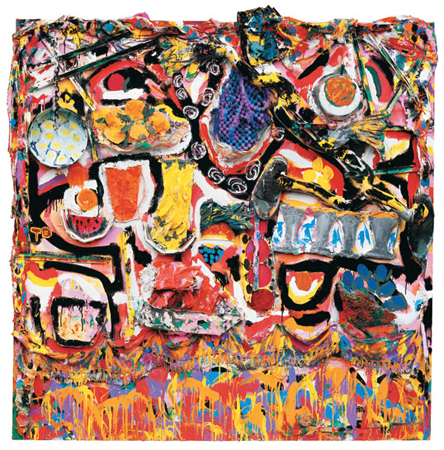

Both artists were influenced by the San Francisco Beat poets and Jack Kerouac’s ‘On the Road’ – De Maria was a professional drummer from high school throughout college, when he got into jazz. Excerpt from an interview conducted in 1972 by Paul Cummings for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution:

You have this sense that all these rivers are going into the Bay and the whole thing is going out to the ocean. So you’re really dominated by the physicality of San Francisco, the sunsets over the bridge, and this incredible nostalgia, this great romantic sense, the fog, the hills, the architecture. You’re just loaded with it, and then the tradition of poetry, the tradition of music, it was like the little cultural capital of the West.

… So if you take all the things together, I would say that coming from an Italian family, growing up in music, having the proximity of the University, having the proximity of all the advantages of San Francisco and there were three museums, not just one. There was the deYoung Legion of Honor. And there were a lot of painters in San Francisco in the area, that being there in the Fifties with the growth of the whole “beat” movement and the growth of the whole black culture and everything, that in a sense I think everybody must have been touched by it. If one had any direction toward the arts at all, as I did initially with music, it wasn’t hard to fall into it because in all it was a fertile, explosive time, even as it continued in the Sixties with the hippies and rock music. It was in a way just a continuation of the Fifties with the jazz and the beats.

By the time I was 21 I had given up the idea that I wanted to teach in the University and so there was this crisis. I had thought that I would probably be a teacher and now what am I going to do? I was getting much closer to living like a musician again, like going out to live as an artist. I think probably the most interesting moment in a young artist’s life is when you really make the decision that that is the way you are going to live.

De Maria spoke about abstract expressionist painting being more like free form jazz, and a form of painting that he could initially get enthusiastic about. However, he grew disallusioned with the painting program at UC Berkeley, and began building small works of wood, moving to NYC in 1961:

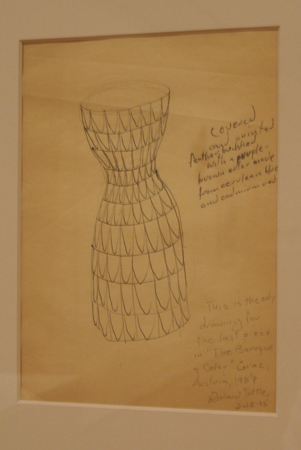

So possibly through the influence of a kind of Japanese sensibility which existed in California, I started to build very small boxes, very clean, quiet, static, non-relational sculptures.

In the summer of Sixty I had drawings and sketches for about 24 so, when I came to New York, I knew that I would not go to he Cedar Bar; I would not seek out all these expressionist painters, these expressionist sculptors, all of these men in their fifties and sixties, just as Lamont probably knew he wouldn’t make music concrete. We started with a very conceptual idea of very limited means, very static, very quiet works. I took a loft and I started. I eventually built about one of these a month; I built about 24 in the first two years I was here, ’61 and ’62.

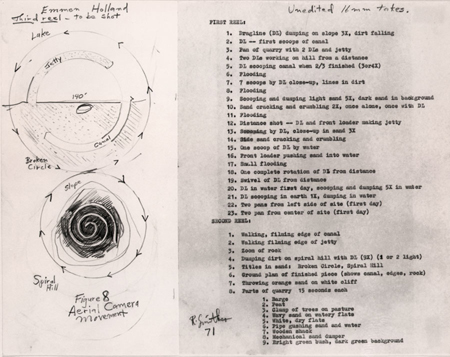

Specifically about his land works, he says:

The point I’m making here is that the most beautiful thing is to experience a work of art over a period of time.

So by starting to work with land sculpture in 1968 I was able to make things of scale completely unknown to this time, and able to occupy people with a single work for periods of up to an entire day. A period could even be longer but in this case if it takes you two hours to go out to the piece and if you take four hours to see the piece and it takes you two hours to go back, you have to spend eight hours with this piece, at least four hours with it immediately, although to some extent the entrance and the exit is part of the experience of the piece.

Smithson’s background was just as important to his future works.

From Robert Smithson’s essays on his site, Fragments of a Conversation, edited by William C. Lipke:

An artist in a sense does not differentiate experience into objects. Everything is a field or maze, and you get that maze, serially, in the salt mine in that one goes from point to point. The seriality bifurcates. Some paths go somewhere, some don’t. You just follow and what you’re left with is like a network or a series of points, and then these points can then be built in conceptual structures.

Oblivion to me is a state when you’re not conscious of the time or space you are in. You’re oblivious to its limitations. Places without meaning, a kind of absent or pointless vanishing point.

There’s no order outside the order of the material.

Every single perception is essentially determinate. It isn’t a question of form or anti-form. It’s a limitation. I’m not all that interested in the problems of form and anti-form, but in limits and how these limits destroy themselves and disappear.

It’s not a matter of what I’d like to do, but how things result. There are strict limits, but they never stop until you do.

Does that mean much to us? These are abstract musings that an art historian could decipher. What really motivated Smithson to create emanates from his childhood, travels in Europe and a dialectic with ‘a kind of anthropormorphic imagery’. An only child, from the time he was seven years old his father took him on visits to the Museum of Natural History.

This 1972Â interview was conducted with Smithson and Paul Cummings for the Archive of American Art/Smithsonian Institution:

I think the strongest impact on me was the Museum of Natural History. My father took me there when I was around seven. I remember he took me first to the Metropolitan which I found kind of dull. I was very interested in natural history…..it was just the whole spectacle, the whole thing- the dinosaurs made a tremendous impression on me. I think this initial impact is still in my psyche. We used to go the Museum of Natural History all the time.

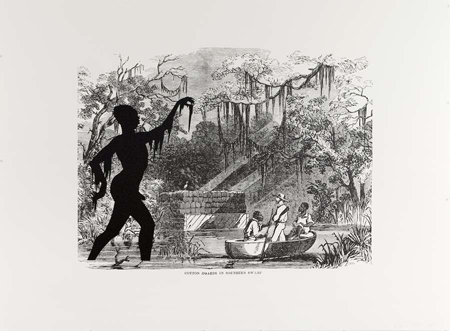

I moved to New York in 1957, right after I got out of the Army. Then I hitchhiked all around the country. I went out West and visited the Hopi Indian Reservation and found that very exciting.

…I knew about Gallup, New Mexico. I knew about and made a special point of going to Canyon de Chelly. I had seen photographs of that. I hiked the length of Canyon the Chelly at that point and slept out. It was the period of the beat generation. When I got back, On the Road was out, and all those people were around, you know, Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, both of whom I met.

I went to Europe in 1961. I was in Rome for about three months. And I visited Siena. I was very interested in the Byzantine. As a result I remember wandering around through these old baroque churches and going through these labyrinthine vaults. At the same time I was reading people liking William Burroughs. It all seemed to coincide in a curious kind of way.

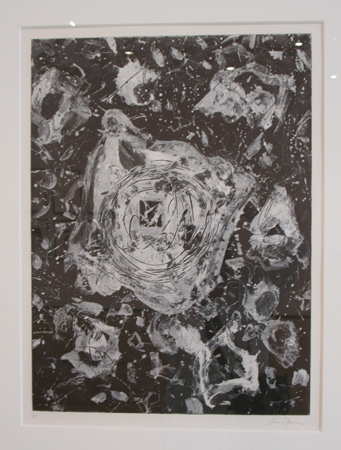

Gradually I recognized an area of abstraction that was really rooted in crystal structure. In fact, I guess the first piece of this sort that I did was in 1964. It was called the Enantiomorphic Chambers. And I think that was the piece that really freed me from all these preoccupations with history; I was dealing with grids and planes and empty surfaces. The crystalline forms suggested mapping.

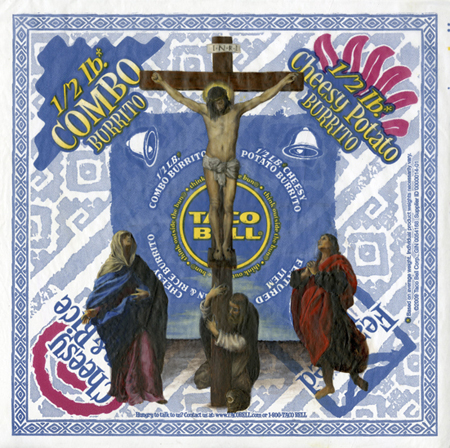

I always had this urge toward all this civilized refuse around. And then I guess the entropy article was more about a kind of built-in obsolescence. In fact I remember I was impressed by Nabokov, who says that the future is the obsolete in reverse. I became more and more interested in the stratifications and the layerings. I think it had something to do with the way crystals build up too.

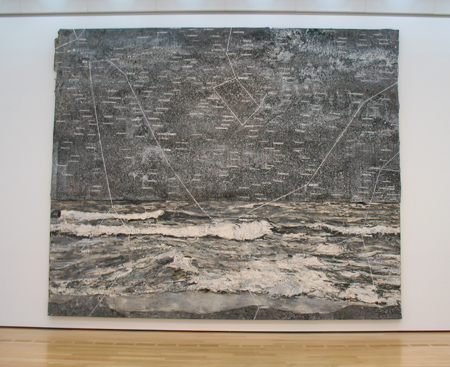

The future is the obsolete in reverse. Dyer articulates the idea of time’s importance in all of these monumental works of earth art; “the accumulated effect of all these comings and goings lingers and seeps down into the foundations, and, weirdly, by falling into ruin the place lays bare its primal circuitry….it retains what D.H. Lawrence called ‘nodality’.”

In tribute to our earth, in homage to its longevity and resilience these works continue to amaze and inform us that we’re specks on the planet and blinks in time.