I’ve been reading about the American painter Fairfield Porter’s life and work and while I knew that he’d once written for Art in America, I hadn’t realized the extent of his interest in philosophy or the range of his intellect. His notion that Plato was all wrong and that ideas cannot be separated between art and reality, along with his perception of science versus the arts, is quite remarkable for the 1940’s and 50’s. I found an excellent source for his papers online at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art.

Another great source for Porter’s interviews and essays is the 1982 book, “Fairfield Porter, Realist Painter in an Age of Abstraction”, by John Ashbery and Kenworth Moffett. In a conversation with Paul Cummings, Porter says:

I think (painting) is a way of making the connection between yourself and everything. You connect yourself to everything that includes yourself by the process of painting. And the person who looks at it gets it vicariously.

When asked if he thought that the person looking had a completely different relationship to the work than the artist, he said:

For one thing they see something the painter hasn’t seen- they are communicated with. They see the person who has painted it and his emotions, which he maybe doesn’t see. When they say they don’t like such and such an art, what they don’t like is something that is really there. It isn’t something that’s imagined.

Some excerpts from papers in the Smithsonian Archives:

When people ask for standards of art, they want to measure it in order to know its limits. The pyschologist E.L. Thorndike contends, “whatever exists at all, exists in some amount”, implying that the existence of art is questionable.  …He expresses the continued scientific prejudice that explanation is what counts most: and that our attitude toward the inexplicable should be to put it temporarily out of our minds. However, because art has so much variety, it is tempting to try to find a common denominator. This is vitality, whose logic is inside itself. You follow your vitality,  you do not tow it behind you. Something is either alive or it is not, and though you can measure an amount of energy, you cannot measure aliveness, which like a chemical reaction, has the quality of wholeness.

As the wholeness of life eludes control, so the wholeness of art eludes the control of the artist. The realist thinks he knows ahead of time what reality is. He refers to it by formal means, and so the work, referring to reality, contains formality.

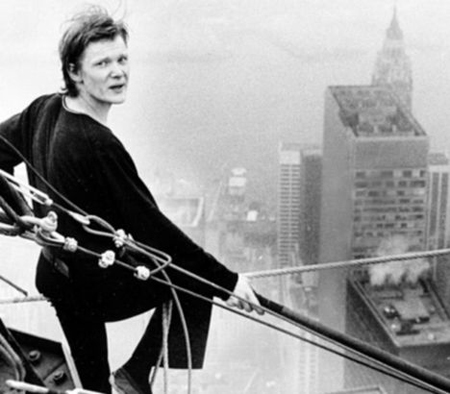

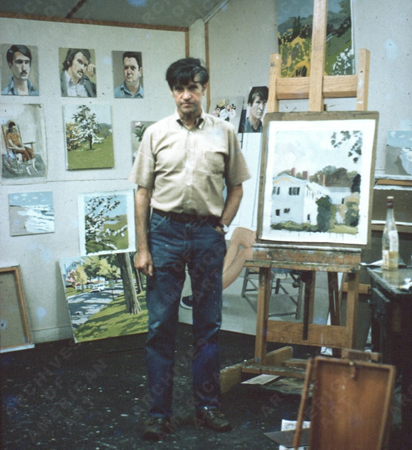

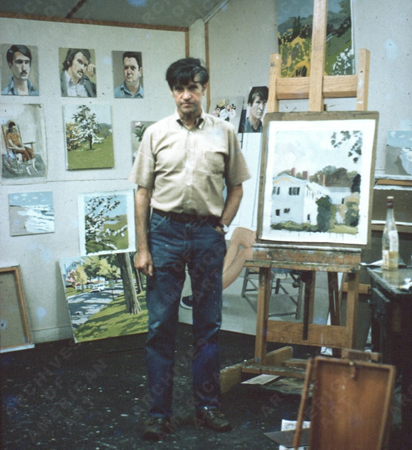

Fairfield Porter in his studio, ca, 1970s, photographer – John Macwhinnie, Archives of American Art. (apologies to Mr. Macwhinnie for not posting credit sooner)

The true and the beautiful become identified in people’s minds at about the same time that they become convinced that the scientific way is the best way to truth. If art is truth and if science leads to truth, then science should lead to art. James Conant in “Modern Science and Modern Man” says that the message of science is that “a continued reduction in the degree of empiricism in our undertakings is both possible and of deep significance” ….and empiricism means to him uncertainty, that is, an “observation of facts apart from principles which explain them, and give the mind an intelligent mastery over them”. Since art is truth, (which science leads to) science should lead to art.

Proof makes science valid. It demonstrates identity in repetition and leads back to the original assumption that nature is uniform. Vitality makes art valid. The characteristic nature of vitality is diversity: nothing repeats itself….The scientist looks for the useful, the artist for disorder. The scientist believe in the existence of whatever he can explain, and thus in a sense, control.

Art as social criticsm is as good as one’s agreement with its message. If art is communication of a message, then the message counts more than its presentation. Art is useful if it tells you something. Certainly that is not information. If it is an idea, then the message that counts is ideal, existing in some intangible place. The ideal can be explained, but presence can only be experienced. You can completely define the immaterial, but what is at hand escapes translation. Science explains -that is, translates and reduces – to give you a substitute for experience. The scientific prejudice tends to dismiss variation.

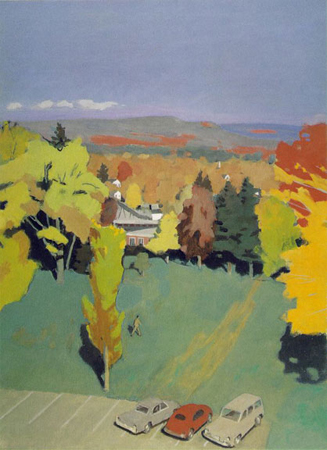

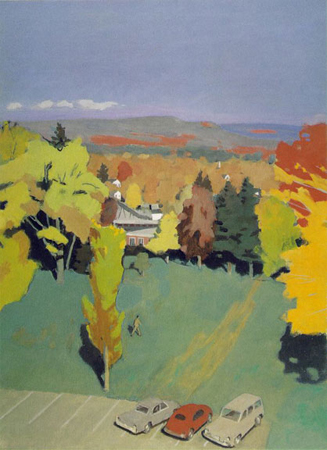

Fairfield Porter, Amherst Campus No 1 1969 oil on canvas, 62-1/4 x 46 inches Collection of Parrish Art Museum, Southampton

Is art the way the idea is presented? Willem de Kooning in 1950 gave a talk at a Museum of Modern Art symposium, and afterwards someone asked him to explain something he had said. “Could you explain it in other words?” His answer was, “It took me two weeks to find out how to say that, and now you ask me to say it differently.” What is said differently does not have its original wholeness and artistically speaking, it is different. You cannot separate the idea from its presentation.

This does not mean that presentation is the essence of art, or that presentation, being method, can be explained by analysis. Too much is left out.

Plato, who thought actuality was the shadow of reality, wished to honor the poets, and then banish them from his Republic. They were a danger to the state. Did Plato understand art to be opposed to the ideal? The Republic finds its closest approximation in the totalitarian state, which show in disguised fashion, Plato’s attitude towards art. They want to use it, and in doing so they make it partial. If what is valuable about art is a reference it makes, then socially speaking, it might better be replaced by this reference. Independence is a necessary condition of the wholeness of art. Art is a threat to the Platonic republic because it says there is something more real than the ideas that command loyalty to such a state.

There is another attitude toward existence than control, namely, respect. The scientist resembles the Platonic social theorist. If you make order important in a Platonic way, you have to close your mind to disorder, as Plato closed his Republic to the poets. There is a nervousness about the uncontained. As tragedy eluded the rationalist, wholeness eludes the pursuit of order.

How can you know the inexplicable? How can you know what art is? I think the…greatest certainty is found in the specific and untranslatable, in experience apart from principles that explain it.

…..Art says the real is specific… The artist can assert the reality of art without reference to anything outside art…Wholeness is as close to you as yourself and  your immediate surroundings. You need not pursue it, you accept it. The real and the alive are concrete and singular. Pasternak said, “Poetry is in the grass.”

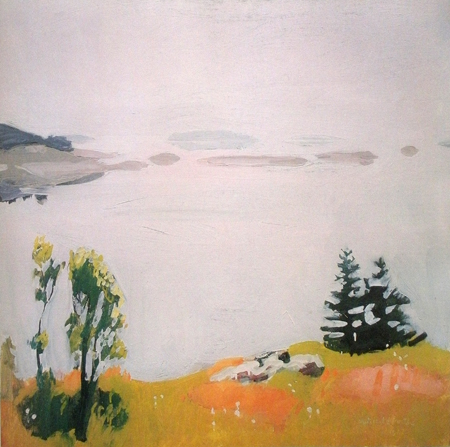

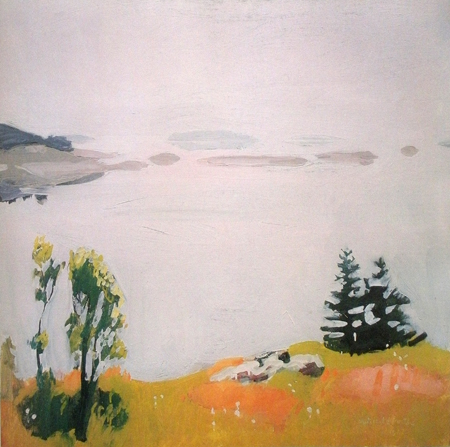

Calm Morning (1961), private collection

Â

Armchair on Porch (1956), Courtesy Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York

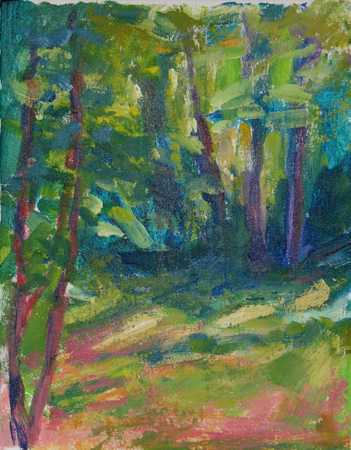

Spring Landscape (1967), private collection

In depth bio of Porter here.