What are the standards for ‘good’ art at the beginning of 2012? A loaded question that probably has a variety of answers for different segments of the population. And how is painting being changed? For an experienced art critic and historian like Robert Hughes, artist Damien Hirst’s work amounts to very little except to enhance the status of collectors who may not even understand his objectives.

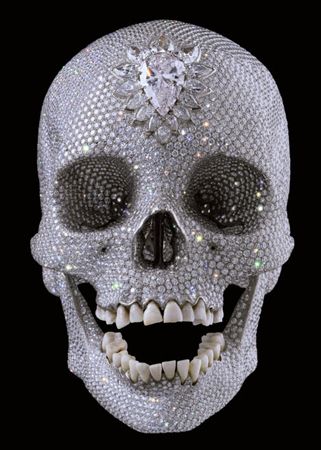

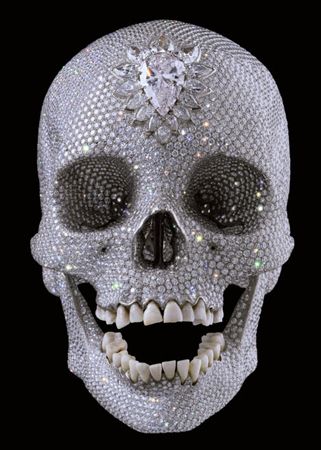

Was Hirst’s 2007 diamond encrusted skull ‘For the Love of God’ presented as homage to the Aztecs as one NY Times review suggested, or was he making a pointed statement about obsessive status in the art world? Or was he simply playing with all the money he’d accumulated over the previous decade?

On the occasion of Hirst’s first solo show of his work in a UK museum at the Tate Modern this April, even the painter David Hockney gets in on the digs against the artist with his slight about craft versus poetry in a radio interview:Â “It’s a little insulting to craftsmen,” he said. “I used to point out, at art school you can teach the craft; it’s the poetry you can’t teach. But now they try to teach the poetry and not the craft.” He quoted a Chinese proverb that to be a painter “you need the eye, the hand and the heart. Two won’t do.”

In a widely circulated video from a couple of years ago, Hughes asks ‘isn’t it a miracle what so much money and so little ability can produce?” as he eyes a Hirst sculpture ‘The Virgin Mother’ that the collector Alberto Mugrabi has installed in the atrium of a building. His summation; ‘It’s just become a kind of bad but useful business’. In the interview he bullies Mugrabi about why he collects art, and cynically laughs as the collector admits that having his impulses as a collector transfer to museum practice could ‘buy immortality’.

While it may be true that some collectors have little knowledge about their purchases, Mugrabi and his collecting father and brother  are reputed to have built the largest and most valuable collection of art in the world. Not every collector should be forced to come up with a dissertation on art theory.

Hirst might best stick to his flashy ironic statements; his recent exhibit of paintings at the Wallace Collection in London was panned as ‘amateurish and adolescent’ in an article by the Guardian’s critic Adrian Searle. This is the same critic who said in his highlights for the arts in 2012 that Yoko Ono’s ‘impact on contemporary art has been described as enormous’.

In Lisa Phillips’ encyclopedic The American Century, Art & Culture 1950-2000, she writes that the 1980s fostered a revival of painting and was the period when art became big business. ‘Artists began taking an active interest in the marketing of their works…Art was not only fashionable and profitable, it was also considered a tangible commodity, and many banks started accepting art as collateral against loans’. If only that were the case for more of us than the Hirsts and Koons of today!

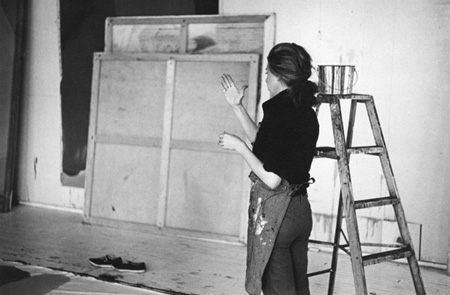

Ok, so what about painting? Painting that requires craft, training and some knowledge of color theory. Or used to.

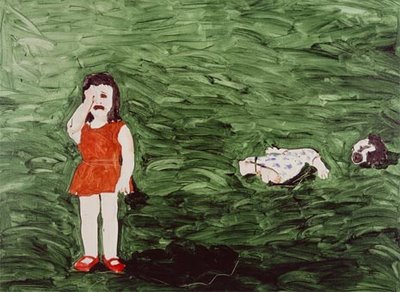

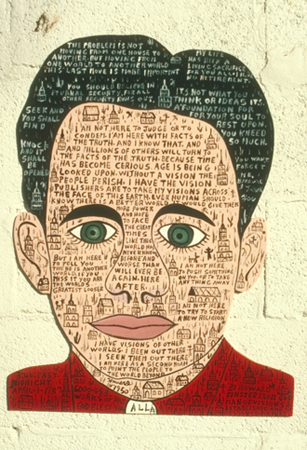

In the late 1970’s the late critic and New Museum founder Marcia Tucker gave the title ‘Bad’ Painting to an exhibition of messy figurative paintings that focused on a ‘deliberate disrepect for recent styles’. Joan Brown, Neil Jenney and William Wegmen were in that first show.

Joan Brown, ‘Girl in Chair’, 1962. Oil on canvas, 60″x48″. Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

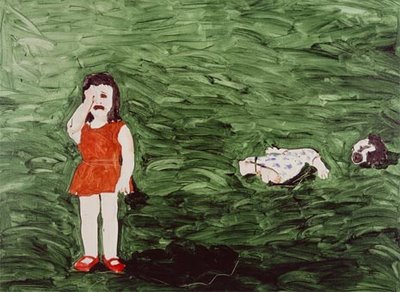

Neil Jenney. Girl and Doll, 1969.

Her notes from the exhibition catalog give us an idea that validation of the work might be an issue for the future:

‘The freedom with which these artists mix classical and popular art-historical sources, kitsch and traditional images, archetypal and personal fantasies, constitutes a rejection of the concept of progress per se. . . . It would seem that, without a specific idea of progress toward a goal, the traditional means of valuing and validating works of art are useless. Bypassing the idea of progress implies an extraordinary freedom to do and to be whatever you want. In part, this is one of the most appealing aspects of “bad” painting – that the ideas of good and bad are flexible and subject to both the immediate and the larger context in which the work is seen.’

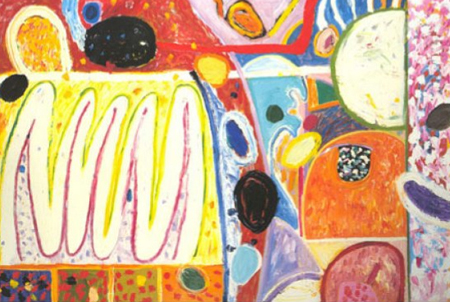

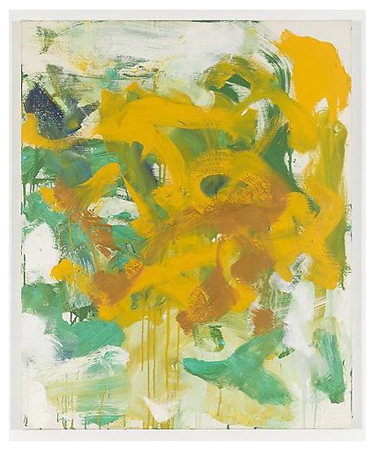

The art professor and prolific blogger Sharon Butler offers a new description for the current style of abstract painter: the Casualist. Butler says in her blog post from this summer: The casualists use earlier abstract styles and motifs intuitively as a visual language rather than as a conceptual premise. Plenty of artists believe in the premeditated strategic employment of references to historic abstraction, but the paintings I’m discussing are more likely to emerge unplanned through the process of painting – not through the focused exploration of a front-loaded conceptual proposition.

All casualists could be called provisional painters, but not all provisional painters are casualists. That many contemporary artists appropriate and strategically quote previous styles is less relevant to the casualists’ way of working than the way Rauschenberg used, say, a tire or a cardboard box. The idea is that meaning emerges from the act of making, not the other way around.Â

I can’t say that I really understand the difference between earlier ‘bad’ painting and the newer ideas of provisional or casualism. And that’s said having some of my work placed in exhibits by curators and artists like Holly Solomon, Miriam Shapiro, Lowery Sims and Linda Cathcart, who were showcasing the trend that merged into Neo-Expressionism during the mid ’80s. Whether meaning emerges from making art or making art creates meaning, the idea doesn’t seem to interest as many painters as it does theorists, curators and writers.

Martin Bromirksi, ‘Untitled’ 2011. Acrylic, sand, paper on canvas 20″x16″.

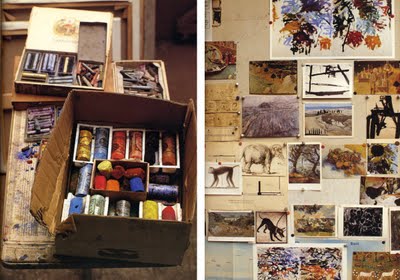

Installation shot from the summer exhibit Painting Expanded at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, Chelsea, NY.

Above: two shots from last summer’s ‘The Painting Show’ at Harris Lieberman Gallery in Chelsea.

Butler’s post elicited some critical responses. One came from the British gallerist Robin Greenwood: By asking if the half-hearted semi-failure of much new abstract painting isn’t “just as interesting†as any stereotypical success, you end up endorsing all its wanton lack of originality. You think that in the deconstructing and re-combining of all the worn-out old modernist tropes there is some original stuff happening? I don’t think so; it all looks horribly familiar to me. And pretty feeble. And even if it’s true that this art is of interest, isn’t “interesting†– in the case of painting – damning it with faint praise? Don’t we want more of art?

Contemporary English and Irish artists represented by Greenwood’s Poussin Gallery in the UK.

Anne Smart. ‘Sudden’, 2009-10. Various media, 152x244cm.

Alan Gouk. “Iris Spin Off”, 2010. Oil on canvas 61x102cm.

Derek Stockley. The Doe Ray Me, 1998. Encaustic on canvas, 124x107cm.

Butler’s response to some of the criticism:

For those who object to the term “casualist,” which PR (particular reader) says implies laziness, “casual†is not an inherently derogatory word. I meant the word to conjure a nonchalant, offhand, and flippant sensibility, but nonetheless a purposeful one–not lazy. The same reader misread the tone of the article as belittling, patronizing and condescending, but actually, I’m fascinated by some of the ideas outlined and am exploring them in the studio myself (although I’m far too much of a handwringer to consider myself a casualist).

In Brett Baker’s Painters’ Table ‘Great Painting Posts from 2011’Â on the Huffington Post, and in an article from Henri Art Magazine, the painter George Hofmann talks about the history and future of Abstract Expressionism and painting.

Abstract Expressionism emerged from the hard confrontations of people who had been born before electric light – theirs was a pioneering effort, and one that required such a tremendous effort and took such a tremendous toll that, perhaps, it was unsustainable. Real feeling, which was the aim, was very, very hard, and still is. Real honesty was very hard, and still is. Â

It was easy to see how Pop could take over – smart-assness can trump real emotion publicly with éclat, and it was much easier to digest for the newly rich who bought paintings not to have to do the hard work of understanding what painters were trying to do…At the same time, the great educational effort in the arts produced a certain intellectualism in artists – the artists now were more and more academically trained, and less the “seat of the pants†types (in Bill Rubin’s phrase) who were the mainstays before.

Finally, he says: …real feeling is difficult – hard for artists and public alike. We have no religion to base it all in, we are swamped by commercialism, and the lack of candor generally itself breeds contempt.

His final words perhaps express the current trajectory that many painters find themselves on;

I also learned to look more closely, and more generously, at what was happening around me: much of what has happened in painting in the last few decades has been, in various ways, involved in the fracture of pictorial space, and although this is not the subject matter of most painting, fractured space has been a hallmark, one probably connected to digitalization, of art for a while now. I think, from a close study of this phenomenon, that what will emerge will be a new conceptualization – a new pictorial space; as in any organic process, old forms die, and new forms emerge from the fallen.

In Paul Corio’s excellent blog No Hassle at the Castle, he posts Hofmann’s ideas on fractured space, which echoes Phillips’ note in her book about various media having entered the field of art. She suggests that a questioning of photographic representation drove many media literate artists, beginning in the 1970s, to redefine and subvert its meaning. Hofmann discusses this changed space with his friends the painters Tom Barron and Arthur Yanoff. Hofmann says:

The world is awash in visual information; unedited and torrential, pixellated, flickering, backlit, and instantaneous. This hasn’t necessarily resulted in greater pictorial literacy, but it probably has affected the way we look at art, and the making of art. In painting it probably accelerated what was already happening: more and more fractured, shifting, unexpected and surprising pictorial space.

Frontality persisted in painting – in Pop, Minimalism, Color Field, even in Conceptual Art – the dominance of the picture plane has ruled since Manet, since Cubism, common to all schools. Color difference and scale alone made for spatiality, so it was mostly through splitting that space could be alluded to; fracturing led to differentiation itself, the breaking-up of space in a shallow field became subject.

…Yanoff notes that newer abstract painting presents a subtle difference from the classical abstraction of previous generations; that there was a sense of wholeness in the relationships in paintings which is no longer part of our experience. The elements in our paintings don’t “lock†now – there is a somewhat disjointed distribution of pictorial elements, a “piling on of history, experience and emotion set the stage for fractured space,” as Yanoff puts it.

Now, it seems, the confrontational/then fractured space we’ve known in painting is giving way to paintings that hint at depth, subtly suggesting it, opening pictures and giving us surfaces that invite us in: in Barron’s words, “we have kept open the cracks, the spaces, the passageways between realities. We don’t cover up or smooth over the seams – we keep the relationships between spaces and forms, the visible and invisible open-ended, malleable, porous and breathing – like life.”

Many contemporary painters in Europe show that vibrancy and intense excitement can still be found in (what appears to be) the simple act of combining color, form and subject. Interesting to me are the similarities between some of these lesser known painters and more commercially successful ones like Gerhard Richter. More about that in a later post.