I’ve been following the Wall Street protests with interest. It’s all over Facebook – friends are engaged in provocative discussions, that show a proclivity to the left, with some right wing antagonism thrown in.

I’m proud of the occupiers; mostly youngsters who are uncertain about whether they’ll ever be able to pay off student loans or whether a job in their chosen field will be in their future. I’m proud of the fact that some of my older friends and acquaintances are going to NYC or to DC or any of the other participating cities, to show solidarity. If I were solidly flush, I’d be there too.

I’m one of the 99er’s, the unemployed millions who benefited from the  (mostly) Democrats’ extensions of insurance for a little over two years, or 99 weeks. That allowed me to look in vain for another broadcast job during those two years, to have time to sell my house in PA – that had depreciated in the failing market – and to begin a tiny art business on December 31st, 2008. Now almost three years later, that very small but growing business may actually sustain me well into the future.

Credit: AP Photo/Andrew Burton

Credit: CBS News/Brian Montopoll

But not many of those millions – often the older workers are booted out first – had my interactive skills, graphic design and web background or retail experience from the many and diverse television jobs that I held over the past 26 years. Not everyone had the benefit of management and software training offered on the job by both small and large companies. I got lucky. The corporations and companies I worked for offered good worker benefits, with top salaries and solid 401k plans. At least until their numbers began falling.

As an artist, early in my career I had to depend on my ‘product’; my prints and paintings, for sole income – so this is nothing new. But for millions who made a lifelong career in the corporate world or manufacturing or car sales or whatever business is now downsizing them – they have few alternatives. Their futures look bleak. Don’t get me started on healthcare reform.

More of the population will side with these protestors than with the top banks and CEO’s of financial firms. CBS News reported that ‘a new survey out from Time Magazine found that 54 percent of Americans have a favorable impression of the protests, while just 23 percent have a negative impression. An NBC/Wall Street Journal survey, meanwhile, found that 37 percent of respondents “tend to support” the movement, while only 18 percent “tend to oppose” it.’

This past Saturday Scott Simon of NPR interviewed Simon Fraser, a professor of history at Columbia University, about the Wall Street protests and what Fraser thought of them.

SIMON: Is this something deeply rooted in American politics?

FRASER: Yeah. What’s going on in Zuccotti Park is indeed deeply rooted in a long tradition of resistance and rebellion really against Wall Street and Wall Street in particular. It goes back all the way, in fact, to the nation’s founding. The first Wall Street panic happened in 1792 just after the birth of the nation. It was set off by an insider trading scheme engineered by a small circle of aristocratic bankers. And when their scheme collapsed and the local economy collapsed along with it, an enraged mob of New York citizens actually chased the leader of this scheme through the streets of New York, probably would have hung him had the sheriff not arrived just in the nick of time and carted him off to debtor’s prison, where he died several years later. And from that moment on, protests directed against the Street particularly has been a recurring feature of American history.

…we spent a long generation – the last 30 years or so – seeing very little resistance, despite the growing disparities and the distribution of incoming wealth and despite the obvious power of the Street in our political system over the last 20 or 30 years. There was very, very little opposition to that, a somewhat mysterious kind of quiescence. But now, shockingly and yet not so shockingly, given the extreme difficult conditions that people face today, that resistance has, so to speak, risen from the ashes and renewed its links to this long live tradition.

SIMON: And do you see it as being at the left or the right or what?

FRASER: You know, I see it as both. After all, the Tea Party, some of the Tea Party, partisans began by denouncing the bailout of Wall Street banks. And I know that in Zuccotti Park there are kinds of people, including Libertarians who resent the fact that the losses of the big banks are being socialized and paid for by American taxpayers while they make off like gangbusters with the profits. So, I think it’s mainly something that’s originating on the left but I think there are some sort of sympathetic echoes in certain circles of the Tea Party movement on the right.

SIMON: And to what degree have these movements recognizing everyone and every generation as different, to what degree have they succeeded, if not outright changing the government but changing policy?

FRASER: Well, that’s a very variable story. Sometimes they have succeeded quite considerably and other times not at all. For example, the Populist movement of the late 19th century, which was a huge political movement that covered much of the Midwest and the South and elected governors and senators and other local officials all across the country, nonetheless had no success in actually weakening the power of Wall Street over the economic and political life of the country. On the other hand, the protests that emerged during the 1930s during the Great Depression had enormous success in reforming our laws so as to reign in the power of the Street. So, the record of success and failure is a spotty one. Sometimes yes, sometimes no.

The History Channel provides an interactive map of New York City’s protests, riots and gatherings for your edification, with events and dates noted.

Earlier this month, another NPR interview was conducted by Guy Raz with Beverly Gage, associate professor of history at Yale and gives us more American history of Wall Street protests:

RAZ: When did Wall Street become a place where protesters gathered?

GAGE: Wall Street really began to consolidate its power as the center of American finance in the years around the Civil War. And then, almost immediately after that, it became a target for protesters, really from a variety of places on the political spectrum. But throughout the late 19th century into the early 20th century, you had very regular demonstrations on Wall Street.

…the first movement that really coalesced around a kind of anti-Wall Street message was the populist movement, which came of age in the late 19th century. And then, by the early 20th century, you have a wave of different movements taking off. You have the rise of the Socialist Party in the United States, for whom Wall Street was the great symbol of American corruption and greed.

And you had the labor movement. And then you also had even more radical movements – to the left, anarchists, communists. But so you have a huge range of people from different positions in American society, with different messages but all really going after Wall Street itself.

RAZ: Much of the movement really culminates in a devastating terror attack in 1920, targeting J.P. Morgan. What happened?

GAGE: Right. That occurred on September 16th, 1920, which was a pretty ordinary Thursday afternoon. And a horse-drawn cart exploded at the corner of Wall and Broad Streets. So, right directly next to the Morgan Bank, very close to the New York Stock Exchange. It ended up killing 38 people and wounding several hundred. And it was by far the most sort of dramatic symbol of this confrontation that had been building for a decade.

Credit – unknown. 1920 Wall Street explosion.

RAZ: The protesters today are mounting nonviolent protests. But what sorts of parallels do you see between those movements back then and what we are seeing today?

GAGE: Well, I think, right, on the question of violence, that was a very different world in the teens and ’20s. And so I don’t think that those kinds of comparisons have much to do with the protesters today…You’ve had lots of different sorts of people involved, and they haven’t always necessarily gotten together around one single piece of legislation.

But nonetheless, they’ve been visible. They’ve pressed questions about inequality, about the role of Wall Street and finance in the American economy, and just big moral questions about what do we want out of our society. And I think those are really the themes that you’re seeing coming out of the Wall Street protests today.

RAZ: Are there clear parallels, in your view, between the economic circumstances of those times and what we’re seeing today?

GAGE: Well, I think it’s really remarkable when you look at the span of the 20th century, we’re really seeing ourselves at the dawn of the 21st century in a lot of similar conditions to what would have seen 100 years ago. In terms of inequality, we have the same kinds of stratifications of wealth that we would have seen 100 years ago – and that actually shrank in the middle of the century, but have since widened back out.

In terms of labor organizing, we have very similar numbers. At their peak in the middle of the 20th century, labor unions recognized or organized about 35 percent of the private sector workforce. At the turn of the 20th century and now back at the turn of the 21st century, those numbers are back down around seven or eight percent.

So I think in terms of economic inequality, in terms of labor organizing, you actually see very, very similar dynamics now.

Credit – unknown.

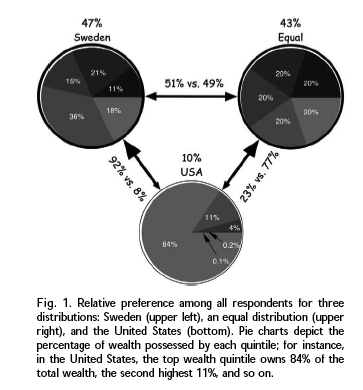

A Duke University 2005 research paper shows the wealth pie chart below that most of you have probably seen circulating on Facebook. The survey asked Americans to construct distributions of wealth that they deemed just, using unlabeled pie charts of wealth distributions – one depicting a perfectly equal distribution, one created from Sweden’s actual income distribution and the third from the US’s distribution.

Randomly drawn from more than 1 million Americans, the authors ensured that all had the same working definition of ‘wealth, also known as net worth, is defined as the total value of everything someone owns minus any debt that he or she owes’. The surprise was that 92% favored Sweden’s distribution over the US’s. Those figures crossed gender and political boundaries.

‘All groups – even the wealthiest respondents – desired a more equal distribution of wealth than what they estimated the current US level to be, and all groups also desired some inequality – even the poorest respondents.’

Finally, what some economists suggest is that a more even distribution of wealth is better for the entire global market, than having the top percentile wealthy. That is a sustainable model, the current one is doomed to implode and die.

Justin Fox, editorial director of the the Harvard Business Review cites economist Mark Thoma in his January 2011 post here:

There is an equivalent of a Laffer curve for inequality, but the variable of interest is economic growth rather than tax revenue. We know that a society with perfect equality does not grow at the fastest possible rate. When everyone gets an equal share of income, people lose the incentive to try and get ahead of others. We also know that a society where one person has almost everything while everyone else struggles to survive — the most unequal distribution of income imaginable — will not grow at the fastest possible rate either. Thus, the growth-maximizing level of inequality must lie somewhere between these two extremes.