Saturday’s SEEK ATL artist studio tour featured Cosmo Whyte’s fantastic studio space downtown, in the Castleberry Hill Arts District. Whyte, born in Jamaica, has widely exhibited in a short period of time and is the recipient of many awards, including the 2018 MOCA GA Working Artist Project (WAP) fellowship grant. He currently teaches art at Morehouse College in Atlanta. SEEK and MOCA GA teamed up this year to visit all three of the current WAP recipients’ studios.

Another older industrial building renovated and put to good use, the downstairs is being divided up into two smaller front spaces, while Cosmo has the use of the large space beyond with the original floor to ceiling windows. I believe he also uses the upper level as a live/work area. My truncated notes from his talk were taken on a scrap of paper, having forgotten my usual notebook.

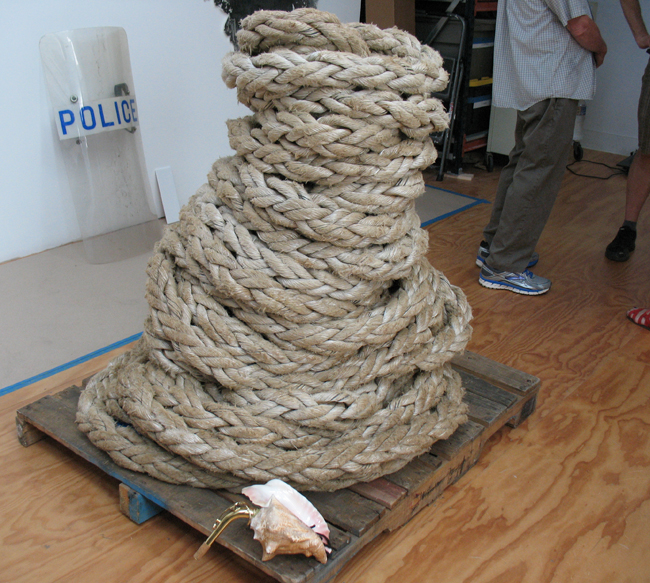

While most of the work currently on view in his studio is unfinished, Whyte is experimenting with various mediums, including braided shipping rope that he purchases off eBay, along with a plexi-glass police shield. The rope is now curled into a large cylinder placed on a wooden pallet, and echoes the braided hair in many of Whyte’s drawings.

While most of the work currently on view in his studio is unfinished, Whyte is experimenting with various mediums, including braided shipping rope that he purchases off eBay, along with a plexi-glass police shield. The rope is now curled into a large cylinder placed on a wooden pallet, and echoes the braided hair in many of Whyte’s drawings.

Ships are what brought the slave-trade to the Americas, rope bound those ships to port and often, the slaves together. A large conch shell sits next to the rope on the pallet. The issue of migration may be at play, whether or not it was forced.

The historic Hatchelling House website states that before the mechanized process was in place, “semi-skilled artisans combed the raw hemp fibre across hatchels, boards with long iron pins to straighten out the fibres before they were spun into yarn. Whale oil, known as ‘train oil’ was used to lubricate the fibres. This was very hard manual work that took great strength…In 1864 the hatchelling operation was mechanised and incorporated in the new Spinning Room built above the Hemp Houses. The hatchellers’ role was passed over to women to work as machine minders following the pattern set in northern textile mills.”

Other ideas for future pieces include Whyte’s plans to laser cut plexiglass, possibly in braille, with snippets of sheet music from “A Ballad for Americansâ€, an operatic folk cantata originally sung by Paul Robeson during FDR’s 1940 campaign against Wendell Wilkie. As a fan of vocal music and of Robeson, I had to do more research.

One line of the cantata reads: “I’m just an Irish, Negro, Jewish, Italian, French and English, Spanish, Russian, Chinese, Polish, Scotch, Hungarian, Swedish, Finnish, Canadian, Greek and Turk and Czech and double-Czech American.â€Â The song was sung at various political conventions in 1940, including both the Communist and Republican conventions, and it endured through World War II, when African American soldiers performed the work in a benefit concert at London’s Royal Albert Hall. It has been periodically revived, during the United States Bicentennial (1976). There is also a well-known recording by civil rights activist and singer Odetta, recorded at Carnegie Hall in 1960. A Wiki link offers more references.

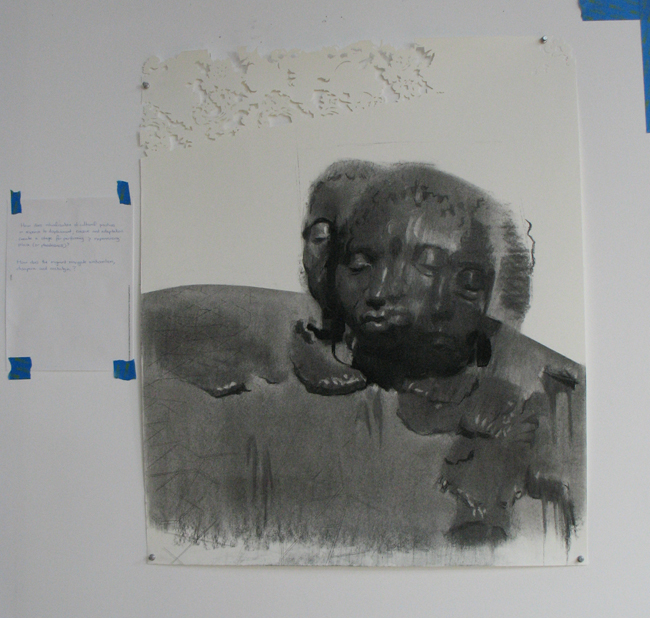

In a couple of large charcoal drawings on heavy paper, Whyte depicts participants covered with motor oil in the Jouvert street festival that many Caribbean islands celebrate. One part of the tradition involves smearing paint, mud or oil on the bodies of participants known as “Jab Jabsâ€, in order to render them invisible or unrecognizable. Whyte said that he wanted to investigate a plantation narrative, with immigrants’ expression of place or placelessness. “Carnival was introduced to Trinidad by French settlers in 1783, a time of slavery. Banned from the masquerade balls of the French, the enslaved people would stage their own mini-carnivals in their backyards — using their own rituals and folklore, but also imitating and sometimes mocking their masters’ behavior at the masquerade balls.â€

In a couple of large charcoal drawings on heavy paper, Whyte depicts participants covered with motor oil in the Jouvert street festival that many Caribbean islands celebrate. One part of the tradition involves smearing paint, mud or oil on the bodies of participants known as “Jab Jabsâ€, in order to render them invisible or unrecognizable. Whyte said that he wanted to investigate a plantation narrative, with immigrants’ expression of place or placelessness. “Carnival was introduced to Trinidad by French settlers in 1783, a time of slavery. Banned from the masquerade balls of the French, the enslaved people would stage their own mini-carnivals in their backyards — using their own rituals and folklore, but also imitating and sometimes mocking their masters’ behavior at the masquerade balls.â€

Security and police presence at these festivals has added another dimension, which may evoke memories of enslavement and/or loss of freedom. Whyte’s said that his depiction of multi-limbed characters is linked to Anansi, the spider trickster of the Ashanti and other Akan-speaking tribes of West Africa, specifically Ghana.

The character is considered to be the spirit of all knowledge of stories, and often the creator of the world. “Anansi is the hero and trickster of an enormous body of West African folktales. Africans had a deep appreciation of mental keenness, as well as sympathy and admiration for those who used their wits to extract themselves from difficult situations. Those who outwitted opponents were respected more than those who outfought them. Cleverness was a trait much revered in African folktales (Ollivier 1994). Hence, Anansi was popular as a small but clever trickster who often outwitted larger opponents.”

Whyte scrapes, sands and cuts away both the edges and main areas some of his work, layering photographic images underneath the cutaway portions. Some of the paper’s edges have a filigree from his cutting away that is reminiscent of lace, which reminds this viewer of the history of women’s work in the textile industry. Lacemaking, long an occupation for upper class women, was a step up for most women during the late 1500s and 1600s, after an Amsterdam town council ordained in 1529 that poor orphan girls would be allowed to make a living from lacework.

Heads may be obscured by braided hair or dreadlocks, features erased or obliterated completely in some of the portraits. He works both from life and from photographs. The result of obvious painstaking work, these figurative abstracted pieces are both powerful and elegant, a tough act to achieve.

Whyte mentioned being interested in the Jamaican scholar Stuart Hall’s writings on transcending nationalism, an aspect that his work seems to address. In the late 1980s, Hall presented a series of lectures called “Cultural Studiesâ€. As this 2017 New Yorker article states, ‘…Hall became fascinated with theories of “receptionâ€â€”how we decode the different messages that culture is telling us, how culture helps us choose our own identities. He wasn’t merely interested in interpreting new forms, such as film or television, using the tools that scholars had previously brought to bear on literature. He was interested in understanding the various political, economic, or social forces that converged in these media. It wasn’t merely the content or the language of the nightly news, or middlebrow magazines, that told us what to think; it was also how they were structured, packaged, and distributed.

“People have to have a language to speak about where they are and what other possible futures are available to them,†he observed…’

Cosmo will participate in The Drawing Center’s Open Sessions 2018-2020 program.

Artist and writer Deanna Sirlin’s review of Whyte’s 2017 exhibit at Marcia Wood gallery can be found here.

SEEK’s next studio visit with be with painter Alan Loehle on Nov. 10th, my 2012 interview with him can be found here.

My history of Pillowtex, an early artists’ space in the same area and now converted to lofts, can be found here.