If you haven’t yet read ‘The Murder of Leo Tolstoy, a forensic investigation‘ by Elif Batuman in this month’s Harper’s, you’re in for a treat. Not only does Ms. Batuman give us a brief history of Russian literature, but she describes the humiliation of walking around the 4 day International Tolstoy Scholar conference in flip-flops and sweatpants, after a luggage mishap with Aeroflot.Â

I loved her writing for this piece; she’s funny, insightful and even brings a Sherlock Holmes story into play in her own detective work for possible suspects in Tolstoy’s murder. If there ever was such a thing. Her tale of a 3 hour bus ride from the conference at Tolstoy’s estate in Yasnaya Polyana out to Chekhov’s former estate, Melikhovo, near Moscow, is not to be missed, despite the yuck factor of a septuagenarian’s hygiene issues. His wife called it ‘the tyranny of the body’.

She admits on her blog that she’s not ‘super-good with facts’ and Harper’s fact checker seems to have had quite a time with her story.Â

‘Probably the biggest disappointment to me during the fact-checking process was the discovery that I fabricated the Lev Tolstoy Accordion Academy—it appears not to exist. Anyone with any information to the contrary should please contact me. There may be a reward.’

John McPhee has written an entertaining little piece on fact checkers in this week’s New Yorker -Â ‘Checkpoints’.

Bravo Ms. Batuman!

Â

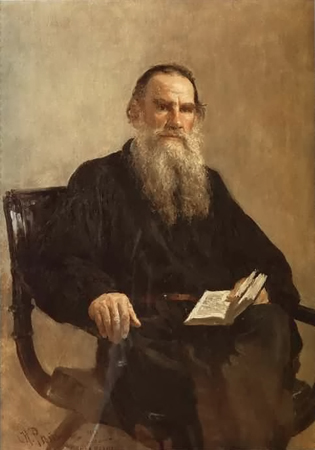

Tolstoy by Ilya Repin

Â

and my favorite Russian artist, Valentin Serov. His portrait of Repin.

I lived in Moscow during a two month period in 1986 when I worked for Turner’s first Goodwill Games, a venture that opened trade with Russia but lost bundles of money for Ted. I ventured out alone to a state run grocery store where customers stood in line for dark Russian bread, where you wouldn’t want to eat the cheese or above ground vegetables since Chernobyl had just blown up.

Every one of our van drivers shuttling us from our hotels to the Ostankino Studio had a large bottle of vodka tucked away behind his passenger seat, to ease the pain of shortage. Few of my other Turner TV colleagues wondered about the Pushkin Museum’s collection or Dostoyevsky or the Bolshoi Ballet, so I visited graves, art and cultural icons alone, struggling to speak Russian from my pocket guidebook.

During my entry into the country, I had been accosted by a young customs official, wanting to know why I was interested in Nabokov’s ‘Speak Memory’, that he found tucked into my clothes. ‘He’s one of your most famous countrymen! Don’t you love his work?’ I demanded, scolding the guard for his paranoia. It was the first of many encounters with what I came to view as a notorious Russian negativity and repression, born of feudalism and failed communism.

One could forgive the curt dismissals, the waving away of our American-ness. We were rich, they were poor. It couldn’t have felt good to beg for chewing gum and Levi’s from a former western enemy. I left the maids my perfume, Belgian chocolate and fashion magazines as tips, since our money was no good to them then.

And despite my hotel phone being bugged, I saw in Russia similarities of culture, warmth and an unbeatable spirit that can be found in the leanest of times here in our own country. The chickens may have been skinny and the dried sturgeon tough, but the vodka flowed freely along with bawdy jokes and irrepressible balalaikas.