Thomas Hart Benton’s paintings of working men and women in his distinctly American landscape have always sparked an emotional reaction in me. They remind me of childhood summers spent in North Carolina tobacco country, at my maternal grandparents’ hand hewn log cabin on their 40 acre farm outside Winston-Salem.

The diverse and urbane culture of Princeton, NJ was my own childhood’s setting, a direct opposite of rural small farm life in the South. New York City was a frequent sojourn for family and school treks, my father commuted to the city as a film editor, my mother took art classes at the Art Students League. Our public schools immersed us in art, taking us children to the Cloisters and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The circular ramp at the Guggenheim remains my first and favorite museum experience; my parents took me there for a birthday treat, a year after it opened in 1959.

Yet North Carolina’s rough talking tabacca chawin’ neighbors, who drove up and down Red Bank Road on their tractors- and my grandparents who were cooking bacon, biscuits and fried apples for breakfast on a cast iron woodstove into the 1960’s – were as big an influence on my young development as was Princeton’s sophistication.

The Ballad of the Jealous Lover of Lone Green Valley, 1934. Thomas Hart Benton  Spencer Museum of Art, U. of Kansas.

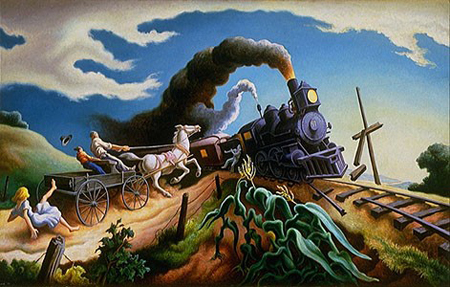

The Wreck of the Ole ’97, 1943. Thomas Hart Benton Hunter Museum of American Art, Chattanooga, TN.

Benton showed compassion in his work for the underbelly of the nation; rolling hills peopled (always peopled) with folks just like my grandparents and their town locals lining the winding country roads. The romance of country living was a fantasy of city dwellers. The realities of the country – lonely boredom, violence, racism and if you were lucky, love – were Benton’s objectives. He succeeded in innovating a first truly American painting, what Henry Adams not so much rhapsodizes about in his 2010 book Tom and Jack, as tells his reader in plain language that any country hick can understand. Was Benton’s philosophy accepted in the art capital, then as now, New York? No, not for a minute. The idea in the 1930s that ruffians and down home carrying on could be suitable for a high art was out of the question.

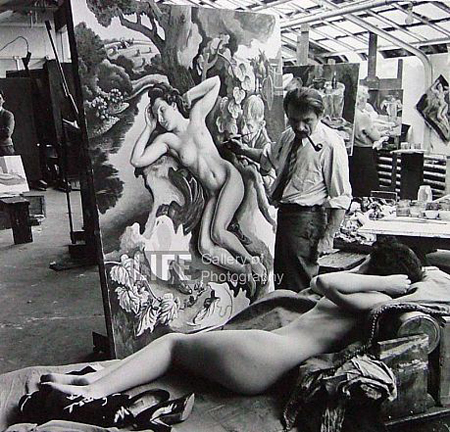

Persephone, 1938-39. Thomas Hart Benton. Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

Benton’s own influences ranged from El Greco, Goya and Tintoretto to a brush with early Cubism. But his ideas and teachings focused on the tenets of Synchromism; what Stanton McDonald-Wright and Morgan Russell had rallied around in their early careers. Adams notes that no other writer connected Pollock with Synchromism, despite Benton’s influence.

Cosmic Synchrony (1913-1914) Morgan Russell – Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute.

As a professor of art history at Case Western Reserve University, and the foremost scholar on Benton, Adams knows his stuff. Andrew Wyeth noted that his book on Thomas Eakins, Eakins Revealed, was the ‘most extraordinary biography I have ever read on an artist’.

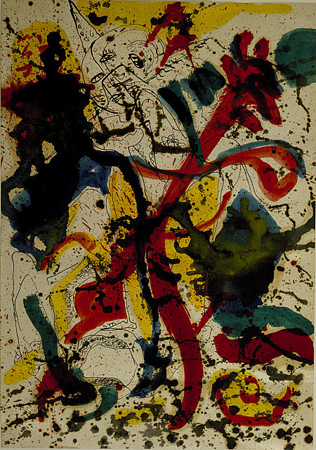

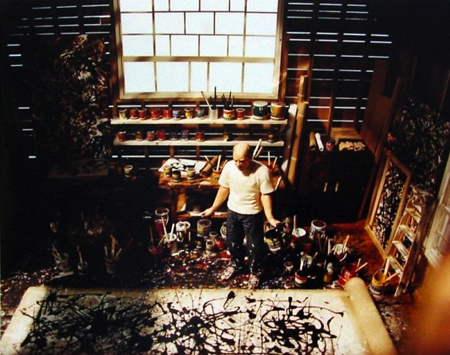

Adams says in his book ‘Tom and Jack’ -Â ‘My point is not that Pollock’s paintings were identical to those of Benton, but something just slightly more subtle and for that reason more difficult for most art historians to grasp: the notion that Benton’s form of composition, his pattern of artistic creativity, and his concept of the artistic self, provided the essential reference point for Pollock’s forward leaps…. Benton’s frameworks were his starting point…One could see that his splashings were not purely chaotic but determined by organizing principles.’

As an artist who has had difficulties in ‘seeing’ Pollock’s work as anything more than drips and relatively meaningless abstractions, this book jump-started the realization that he indeed was taking off from representation. His own personal symbolism, iconography and ‘borrowed’ appropriations from Benton and modern art became fodder for these wildly gestural pieces.

Untitled (1942-44) Jackson Pollock – National Galleries of Scotland.

Mural (1943) Jackson Pollock – University of Iowa Museum of Art.

In one of his last chapters on Pollock, Adams makes the observation that forgeries ‘generally look all right for a few minutes, but very quickly they become boring. We soon see that they are made up of repetitive gestures. They represent nothing of significance, and the gestures, while initially arresting, soon reveal themselves as superficial and tiresome. …Pollock’s drip paintings at their most basic underlying level are ghost-like Benton figure paintings, which are then pushed to even a higher level of generalization. Because they have this imagery and meaning, even though it is difficult to fully discern, they are not dull and repetitive but are filled with inner life.’

Tom Ball, a Cleveland filmmaker, produced a wonderful film clip of Adams talking about Benton and Pollock on his own fascinating blog.

The Jackson Pollock Code from Thomas Ball on Vimeo.

You can watch a former student and a friend of Benton’s talking about his work, in the PBS aired Burns’ 1988 film, here. In Kirk Varnedoe’s excellent 1999 book, ‘Jackson Pollock’, Pollock himself ascertains that he is a representative painter. But while he was aligned with the NY School of Abstract Expressionists, he fought any definite label except the avowal that he was the greatest living painter of the era. A PBS interview with Varnedoe can be found here.

Thanks for making an unusual but convincing connection between two great American painters. While the connection between Benton and Pollock may not be intuitive, I experienced something similar about 20 years ago. Upon seeing a large mural by Pollock– I can’t remember the museum– I immediately saw an echo of Picasso’s Guernica. The painting bore the same title, and I was stunned at how Pollock, at his level of high abstraction, was able to capture the structure and drama of his referent. Thus it’s not hard for me to be convinced by Adams’ arguments.

It was amusing, too, to hear that Benton’s lyrical depictions of rural life were deemed inappropriate decades after the Impressionists fought the same battle!

Benton was Pollock’s teacher, thus the initial connection. Pollock also played off Picasso in some of his early works, you’re right- it’s obvious.